Free Our Vote

Represent Justice’s Surrogates and Ambassadors are proud to present FREE OUR VOTE, a guide to voting for and by people impacted by the justice system. This guide offers historical context for disenfranchisement, explain who may be on the ballot and why they are important, as well as how to find out if you are eligible to vote in your state and what your rights are once you are registered. Below you can find printable one pagers and a tri-fold pamphlet along with downloadable social media graphics for you to use.

How We Got Here

The United States has one of the most punitive legal systems in the world. It has the highest rate of incarceration in the world, and Black Americans make up 33% of incarcerated populations, despite comprising 12% of the total adult population. The United States also restricts the voting rights of system-impacted people, in many cases preventing citizens with felony convictions from casting votes. According to the Sentencing Project, 5.2 million Americans with felony convictions had lost the right to vote as of 2020. One in every 16 Black adults has been disenfranchised for this reason — a rate four times greater than non-Black Americans.

This severe approach to punishment is embedded in the fabric of our country — “civil death,” or the practice of revoking voting rights as a criminal penalty arrived with English colonists. The first felony disenfranchisement law was passed in 1792 in Kentucky. Other states followed suit, and by 1870, 28 out of the then-38 states had similar legislation.

It’s impossible to separate the practice of felony disenfranchisement from the systemic racism of the United States. There is a direct link between the end of the Civil War in 1865 and the increase in felony disenfranchisement laws. Three years after the 13th Amendment was ratified and slavery was abolished — except in the case of punishment for a crime — the 14th Amendment cemented felony disenfranchisement as a legal practice in the Constitution. While the 14th Amendment granted citizenship to all people born or naturalized in the United States, the amendment also gave states the power to deny citizens voting rights for “participation in rebellion or other crime.” This loophole cemented the practice of felony disenfranchisement in the United States.

Revoking voting rights, among other penalties, became a new way to legally restrict the freedom of Black Americans. States crafted disenfranchisement laws to target Black people with severe and disproportionate penalties for small, petty crimes, and systematically limited Black voters through poll taxes, grandfather clauses, and literacy tests. These practices were a part of the patchwork of Jim Crow laws and Black codes designed to rob Black Americans of their rights.

The hard-won Voting Rights Act of 1965 was meant to counter this theft of electoral power and ensure everyone has the right to vote. However, a 1974 Supreme Court decision in the case of Richardson v. Ramirez upheld state rights to disenfranchise people convicted of a crime.

Since 1997, we’ve seen laws change in more than half of states that either restore voting rights, simplify the process of restoring voting rights, or reduce the restrictions. Because of these modifications to felony disenfranchisement laws, an estimated more than 1 million people have regained the right to vote.

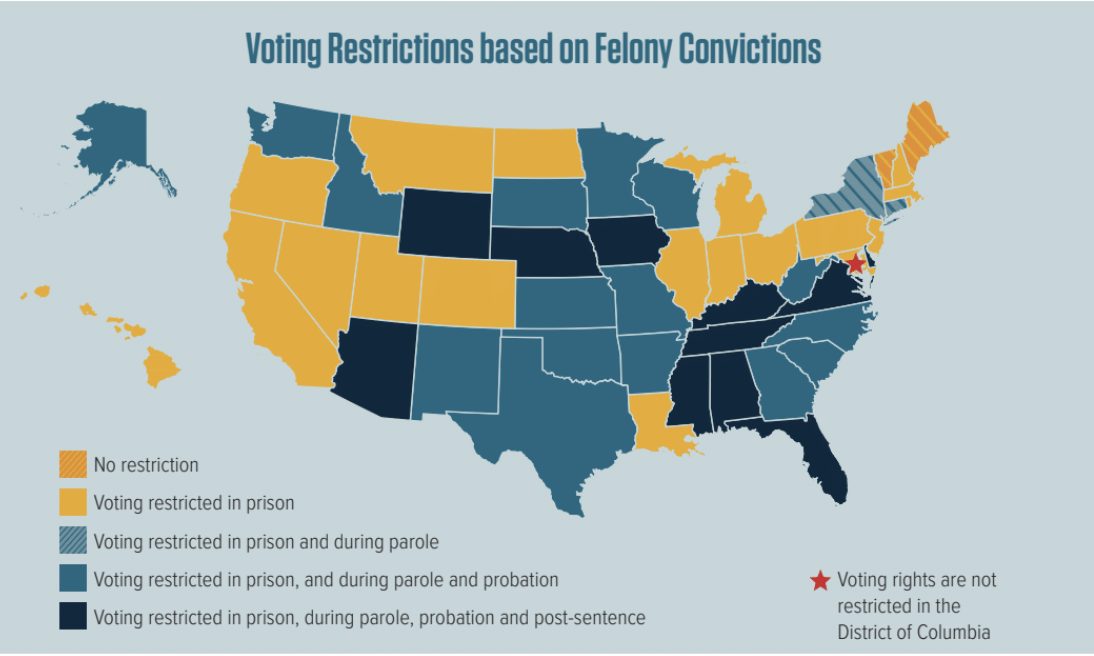

However, such progress is not enough when more states need greater voter representation for candidates to uphold the rights and needs of voters they are responsible for. There are only two states — Maine and Vermont, and the District of Columbia — where system-impacted people never lose the right to vote and are allowed to vote by absentee ballot while incarcerated. By contrast, 26 states currently prohibit people from voting if they’re on probation, parole, or have completed their sentence. This means approximately 1 in 44 adults can’t vote because of a current or prior felony conviction. Of this population, over one million are Black people who have completed their sentence. Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, Virginia, and Wyoming have the highest rates of disenfranchisement in the country.

Attempts to do away with felony disenfranchisement at the federal level have failed, creating a patchwork of laws and policies that vary wildly from state to state. Even those living in a state with less restrictions around voting rights face a complicated pathway to getting lost voting rights restored.

Breaking Down the Ballot

There are many elected officials that work within the criminal justice system. Some of these officials are well-known roles like the President and members of Congress, but there are many other officials on ballots that have a significant impact on the direction of our system. However, knowing who you get to vote for and what each position does can be complicated. The duties of these positions can change from state to state, and certain positions, like judges, aren’t on the ballot in every state.

Below, we lay out a few key positions to be aware of before you vote. We encourage you to do more research into the specific candidates in your district. You can look up your ballot and compare the candidates.

Judges

Judges preside over court proceedings and are in charge of the interpretation and application of the law. Their powers, functions, training, and methods of appointment differ by jurisdiction, the geographic area where they have legal authority.

Federal judges are appointed for life by the President, but almost all state court judges are elected. The length of judges’ terms varies from state to state. About 85% of criminal cases are decided in the state system, which means these judges hold a lot of power. Judges are not always allowed leeway in their sentencing guidelines, but it is important to seek out a judge’s general stance on criminal justice reform before heading to the polls. You can search judges online to get a sense of their judicial record, and even read some of their published opinions to get an idea of how they interpret and apply the law.

Prosecutors

Prosecutors, sometimes called State Attorneys or District Attorneys, are elected officials that prosecute criminal cases. Despite the enormous power and influence of prosecutors in the justice system, 84% of prosecutors run unopposed nationwide.

In criminal cases, it is the prosecutor who decides to file criminal charges and the severity of those charges. They can also decide to instead route people into a diversion program to help them rebuild their lives, or to have charges dismissed. And, their power varies state by state. Prosecutors may have discretion to involve Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in cases and set into action deportation proceedings; to direct people to mental health and substance use programs instead of prisons to prosecute police for officer-involved shootings; and to implement policies that end cash bail and curb pretrial detention.

Sheriffs

Sheriffs are typically elected and preside over a county where they investigate crimes, oversee local jails, and manage the transportation of pretrial detainees. Local sheriffs are a presence in every state except Alaska, Hawaii, and Connecticut, which rely on state law enforcement agencies.

Prior training or experience in law enforcement is not always a requirement to be elected sheriff. Some candidates come to the position with backgrounds in business, real estate, or even academia. Depending on the county, sheriffs can control if people in jail are allowed to vote, if they coordinate with ICE, and much more. Many sheriffs can serve for long periods of time, often with few checks on their authority, since unlike police chiefs, sheriffs typically do not report to mayors or other elected officials.

Mayors

Mayors are the elected heads of a city, town, or municipality. Typically, mayors appoint the chief of police in their city and have a say in police practices and the police department’s budget. Mayors can also enact policies that have outsized impacts on the local criminal justice system, such as a stop and frisk policy which leads to a documented rise in racial profiling and the disproportionate criminalization of Black and Latino people. Or the Mayor could implement additional mental-health training for the city’s officers and establish reconciliation sessions between community groups and police officers to rebuild trust.

Local Government

Depending on where you live, there are different bodies of local government that have a hand in shaping your community’s justice system. City councils — sometimes called town boards or Board of supervisors — are one important body composed of elected council members from the community. City councils are responsible for proposing and passing bills, laws and resolutions that help govern the city. Often, the mayor sits on the city council but whether they have a vote on legislation that comes through the council varies across each town and city.

City councils can have the power to close jails, expand the use of alternatives to jail and redirect resources to social services like mental health treatment, housing and substance use programs.

Governors

Governors are the elected executive head of each state. Governors are responsible for implementing state laws and overseeing the state’s executive branch. They often appoint a number of state officials and decision makers, like judges, agency heads, and parole board members.

Governors have the power to grant clemency in their states for people convicted of felonies who have received extreme or unfair sentences. Clemency can be granted through a number of ways. Governors can choose to commute a person’s sentence, which reduces the amount of time served but does not declare them innocent. Or, they can pardon someone by canceling a legal judgement and declaring a person not guilty. Governors can also issue executive orders that can steer a state’s justice system toward reform.

How to Vote

Check if you’re eligible to vote

For system-impacted citizens, learning if you can vote can be complicated or confusing. In some states, those with felony convictions might not be eligible to register to vote, but in other states they are eligible. Today, a number of states are restoring the right to vote for those who have completed their sentence.

You can find out if you are eligible to vote by visiting Campaign Legal Center and using their free tool: Restore Your Vote. If you run into trouble using this tool, or have a question about your convictions you can also call (888) 306-8683 (toll-free) or email [email protected].

Register to vote

If you are eligible to register to vote, you can do so online in most states at: https://vote.gov/. Registering to vote is simple — all you’d need to provide is your name, address and social security number or ID number.

If you’d like to register to vote in-person, you can visit your state or local election office or often the DMV. Find your local election office here: https://www.usa.gov/election-office

Every state except North Dakota requires citizens to register if they want to become voters. Deadlines for voter registration vary by state — from over a month ahead of the election to same-day registration. Check the US Vote Foundation to find your state’s requirements.

At the polls

If you are planning on voting in-person in November, you may need to prepare to arrive at your polling place with photo ID or proof of residence. To check what is required in your state, visit: https://www.rockthevote.org/how-to-vote/

Voting by mail is an option for casting your ballot. Voters in 45 states and the District of Columbia will also be able to vote by mail. However, voters in 16 states must qualify before receiving an absentee ballot. Check if that’s your state here. To learn more about your state’s rules and how you can sign up to vote by mail, or request a ballot click here or go to your state election office website to find out how and where to drop your ballot off.

Some states have proposed new legislation in 2021 that may impact absentee or early voting. Be sure to stay informed this election cycle and check with your local news outlets

Know your rights at the polls

Due to an uptick in restrictive voting laws, it’s critical to know what your rights are before you head to the polls.

- If the polls close while you’re still in line, you still have the right to cast your ballot.

- You can request a new ballot if you make a mistake on yours.

- You don’t have to speak English to vote. Federal law says voters who have a hard time reading or writing in English can receive in-person help at the polls from a person of their choice.

If your poll worker says your name isn’t on the list of registered voters, you can:

- Ask them to double check.

- Ask for a supplemental list of voters.

- Ask them to help you confirm you are at the correct polling place.

- Ask for a provisional ballot. If you are eligible and registered to vote, officials are required to count your provisional ballot.

If you are a voter with a disability, you can:

- Bring a friend or family member to assist you at the polls. Just be sure to let the poll worker know you’ve brought someone to help.

- Ask a poll worker to meet your needs. If the lines are long and you can’t stand, an official can bring you a chair. If you need a quiet place to vote, an election official is required to make reasonable accommodations to help you vote.

If you have questions on Election Day or witness or experience harassment on your way to vote, you can call the Election Protection Hotline.

- English: 1-866-OUR-VOTE / 1-866-687-8683

- Spanish: 1-888-VE-Y-VOTA / 1-888-839-8682

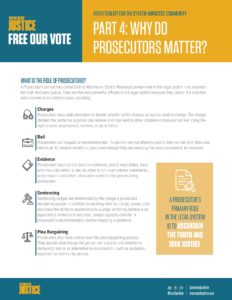

What is the role of prosecutors?

A Prosecutor’s (sometimes called District Attorney or State’s Attorneys) primary role in the legal system is to ascertain the truth and seek justice. They are the most powerful officials in the legal system because they control the direction and outcome of all criminal cases, including:

- Charges: Prosecutors have wide discretion to decide whether to file charges as well as what to charge. The charge dictates the sentence a person can receive and may lead to other collateral consequences like losing the right to vote, employment, eviction, or deportation.

- Bail: Prosecutors can request or recommend bail. If a person can not afford to post it, they can be (and often are) held in jail for several months or years even though they are awaiting trial and presumed to be innocent.

- Evidence: Prosecutors have control over the evidence, and in most states, have enormous discretion to decide when to turn over witness statements, police reports and other information useful to the person being prosecuted.

- Sentencing: Sentencing ranges are determined by the charge a prosecutor decides to pursue. In addition to deciding what to charge, prosecutors also have the ability to recommend to a judge what they believe is an appropriate sentence in any case. Judges typically consider a prosecutor’s recommendation before imposing a sentence.

- Plea Bargaining: Prosecutors also have control over the plea bargaining process. They decide what charge the person will plead to and whether to demand prison or an alternative to incarceration, such as probation, treatment or community service.

Why you should vote for your prosecutor

Traditionally, prosecutors have used their power in ways that contribute to overcriminalization and collateral consequences — such as evictions, felony disenfranchisement and deportation — and the ever-increasing use of incarceration over other less harmful alternatives. As a voter, you have the power to hold them accountable. By using the power of your vote, you can demand they use their office to change the way the legal system operates and end mass incarceration.

What to look for in a reform-minded prosecutor?

Prosecutors play a dominant role in the legal process through the exercise of their broad, unchecked discretion. Given these powers, prosecutors are in the best position to make policy changes that can roll back over-incarceration and improve the overall fairness and efficacy of the legal system. Some of the things to look for in a reform-minded prosecutorial candidate include someone who:

- Engages with the community

- Critically questions accusations

- Uses restraint when making charging decisions

- Is fair when plea bargaining

- Holds police accountable

- Seeks truth over convictions

- Considers fairness over punishment

- Thinks creatively and realistically about public safety without resorting to fear and rhetoric

- Addresses racial disparities in the legal system

- Changes office culture and practice

- Creates effective sentencing and conviction review

- Does not criminalize mental illness, drug addiction or poverty

- Prioritizes diversion, alternatives to incarceration, and violence interruption programs

- Promotes Restorative Justice

- Treats children like children, not miniature adults

- Accounts for the collateral consequences to criminal convictions

- Supports expungement and sealing of criminal records

- Challenges the status quo

Prosecutor impact outside of the courthouse

The power and influence prosecutors wield extends beyond the courthouse. They do not just enforce laws, they also influence the people who make them. Prosecutors frequently lobby local, state, and federal legislators in support of or in opposition to proposed legislation.

As public officials, prosecutors also have a huge influence over the public’s perceptions of rising crime rates and definitions of public safety. This is in large part due to the media’s over-reliance on prosecutors and police as their sole source for crime reporting — we’ve seen it in everything from daily crime stories to the media framing of the case of the Central Park Five. As members of the law enforcement community, prosecutors have unique insights and perspectives that are highly influential in shaping the media and the public views on what people think about crime, how they think about it, and what solutions seem desirable.