Malika and Lydia of Apart share how they navigated their reentry journeys

The documentary Apart follows the story of three mothers incarcerated in Ohio — Tomika, Lydia, and Amanda — as they prepare to return home from prison and work to rebuild their lives after being separated from their children for years.

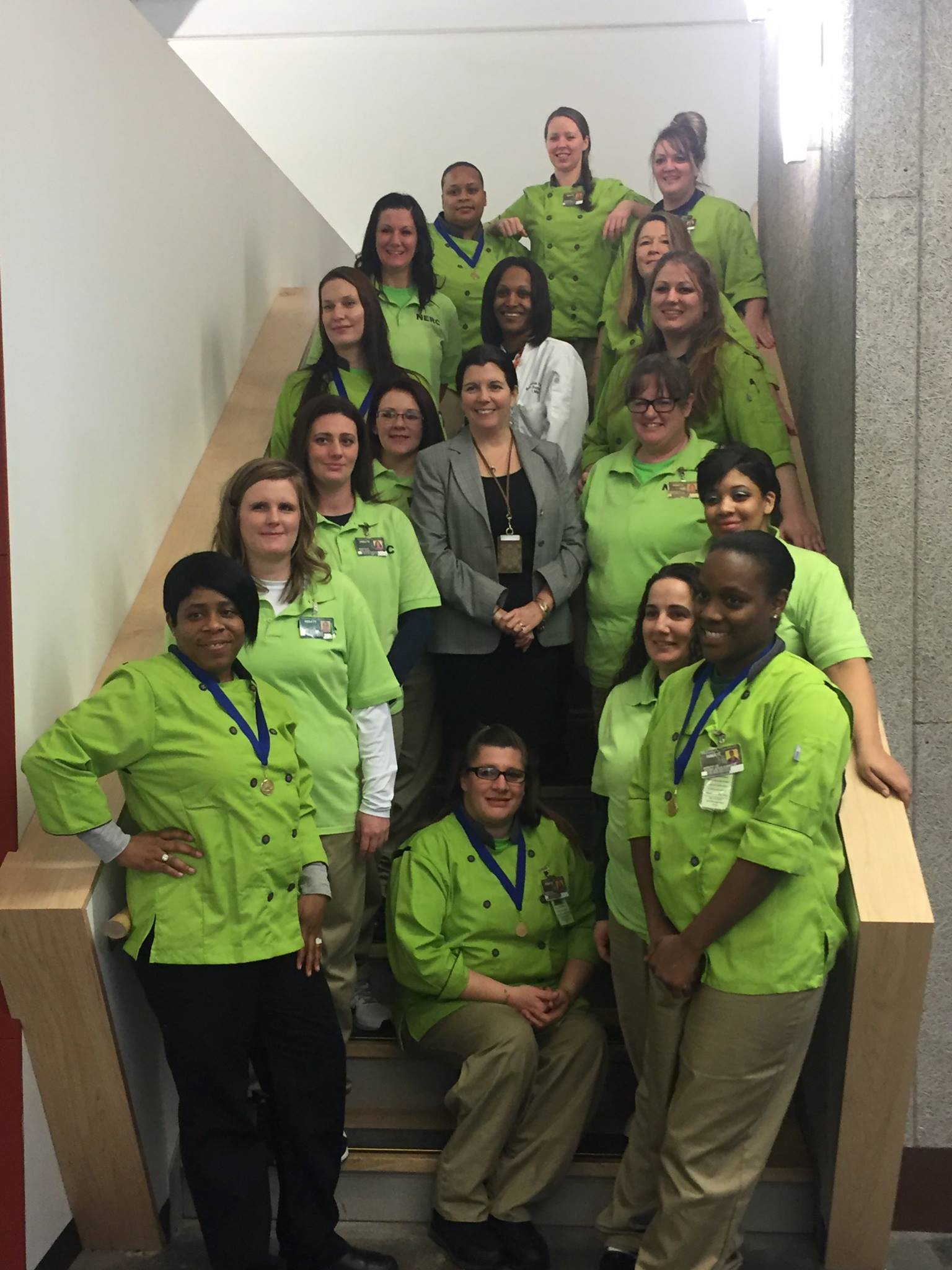

As part of their reentry journey, they participated in Chopping for Change, a workforce development program for incarcerated women headed by Malika Kidd, who is formerly incarcerated herself. The program allowed them to build skills, connect with other women and begin healing from their past experiences as they prepared to head home to their families.

Malika and Lydia recently got together to talk about the challenges they faced in their reentry process, and how typical hurdles like finding employment, housing, or even figuring out how to get yourself around become much harder to tackle for women.

Read their conversation below. The interview has been edited for brevity.

Malika: Hi, Lydia, how’s it going with you and your family? How’s the hubby?

Lydia: Oh, it’s not, you know, not too bad. A little crazy here and there. He has been in and out of the hospital since Christmas and he was having all the seizures for the last month and a half. It’s actually gotten to the point where my son and I can’t handle taking care of him. So he is being moved to a skilled nursing facility, hopefully today, just so he can do rehab and get a little bit stronger. The seizures just really caused a lot of issues on top of issues he was already having.

Malika: A lot of people are actually praying for him and asking about him on some of the panels, just so you know.

So what were you most worried about when you were preparing to reenter the workforce?

L: Everything. Literally. I mean, even in the documentary, the last thing I wanted to do was go out and explain that I had a felony and try to make it sound okay. I was really kind of worried that no one would want to hire me, and that I’d never find a decent job.

M: While I was still incarcerated, an organization had promised me a job once I was released. And then when I got released, they were like, we don’t have the funding to pay you, and so that was so disheartening. When I got out I had a lot of little odds and end jobs, but they didn’t ask that question. And then the job I have now, they already knew I had a felony and that’s what they wanted — someone with the lived experience to run the Chopping for Change Program.

L: When I got to Tim Hortons, the owner, actually, he loved the halfway house girls. He knew all we want to do is work to not be at the halfway house. So. But he did ask, “What did you do? Why were you in prison? Are you going to go back to that? Did you learn your lesson?” He definitely had his eye on all of us when we first started. But within a month, he was talking about making me a manager. So I didn’t have to prove myself, but I had to get myself in the door to prove myself.

M: I felt like I had three strikes against me: I’m a woman, I’m African American, and I have a felony. So I have to work three times as hard as someone else. Even in the position that I have now, the person who had this position before me only has some college courses, not even a degree. I worked my butt off to get an Associate’s and Bachelor’s, and now I’m working on my Master’s, just to have my foot in the door.

L: Right. I already have my bachelor’s, but starting out in jobs like that most of them don’t care. A lot of times, when we’re getting out of prison, the only jobs we’re getting are within food.

And then I found as much as companies say they’re felon friendly, they are felon specific. Like [my felony conviction] being receiving stolen property – it’s considered theft. That means most places aren’t gonna hire you. But if you have a child endangerment, which is a way worse felony, they’d hire you. There’s no rhyme or reason to it.

How can you move on from your past, if you can’t get your foot in the door to build a future?

Malika Kidd at the premiere of the breakout short for Apart.

M: So what was helpful to your reentry journey?

L: Having to go through those groups [at Lutheran Metropolitan Ministry] and intensely look at yourself forced you to deal with a lot of things and realize what’s important and what’s not. And to know that stuff just doesn’t stay the same, stuff is always changing and nothing is always going to be that way. Things always get better. That, and my own drive, not wanting to be in the halfway house and go back to prison. The sooner I had a job, the sooner I would be able to get home to my family. I never wanted to go back to prison ever again.

L: What barriers did you face in your reentry journey? What did you wish you and others could have had access to that would have helped?

M: Housing: paying application fee after application fee. Although I had family support, you know, they were all in Illinois, and I decided to stay here in Ohio. So transportation was a barrier, especially on the city bus with other people who sometimes act a little crazy. I literally had to threaten somebody to spray with mace even though I didn’t have any.

L: How about taking basically like two to four to six extra hours to get around because you have to ride the bus.

M: It took me two hours to get to the job, and I only worked like four hours. So I spent more time on the bus than I did on some of those jobs.

Or even with parole officers. My first parole officer was horrible. She just made up her own rules as she went along. She even put me on an ankle monitor when I first came home because I was from out of state. And then two weeks after I was released, I was asked to come back to the prison and speak to some people they had there, and the alarm went off because I had an ankle monitor on. They explained that it wasn’t a rule, she just did it. A week later they removed it.

Parole officers can be quite difficult. Even after I got this job, going in there to see them, you could sit there for hours. I was fortunate and blessed enough to have an understanding employer. But what about those who don’t?

L: Yeah, because there’s a lot of them that don’t. They don’t treat people fairly in any way, shape or form. Luckily, I didn’t have to deal with a parole officer, but I did have the case managers at the halfway house that I had to go check in with all the time. And they weren’t quite as bad, but they weren’t that great, either.

M: Like even with the ladies coming home now. We have a job for them. Trying to find housing is becoming a hard thing. And not just any housing but in a nice quality area. Yeah, I know. Some landlords will rent, but it’s an area that is high risk where they might get in trouble or go back to using drugs.

L: Or they’re just not in a good environment. They could get attacked as women walking in a neighborhood that’s not good at night, or early in the morning trying to get to work or to that bus two hours early.

I had to walk all through downtown, on the worst side of town. You literally had to walk through the entire city to the center just to get on the bus.

Lydia Loth, third from the bottom on the left, joins other women at their graduation from the Chopping for Change program.

M: What impact did the Chopping for Change Program have on you?

L: Man, the Chopping for change program had a lot of different impacts. The groups really gave me a chance to kind of look at things from a different perspective. Ms. Cheryl was amazing, especially being in recovery herself, you know, she kind of understood.

Even, as much as they drove me crazy, the bond with the other ladies in there. We’re learning all about them and their life and things that they had been through and how they had dealt with it. And their trauma and their stress and their worries. Everybody’s kind of all the same. I mean, the situation is different, but the worries and the stress are all the same.

M: What are some unique challenges that women face when it comes to reentry?

L: Being a woman in general is pretty much held against you right from the start. You’re instantly looked at as weaker, and then to have a felony on top of it, trying to do reentry. A lot of people kind of look at it, like, “Oh, they got wrapped up with some man and, you know, they can’t stand up for themselves.” Almost like they can be taken advantage of or controlled in some way.

M: Yeah, most women coming out, they are the primary caregivers for their kids. And whoever has their kids [while they’re incarcerated] is like “here, you go, take them back.” And once again, it’s hard to get housing. Or if you’re in a halfway house, your child can’t go there with you.

L: Even in the halfway house, they don’t even give you a chance to bond with your kids in any way, shape or form while you’re there. With [my children], when they had sports and stuff I couldn’t go even if I was off work. Even with an ankle monitor on I couldn’t go. Stuff at their school, I couldn’t go. You really don’t get to be involved in their life in any way, other than visiting, which is really hard to be on the outside and not be able to be with them.

M: And in health care, too. I was fortunate because when I came home, we were able to sign up for Obamacare. I went straight to the doctor to get a physical, because when I was in there the last year, the doctor told me I had this disease that I did not have. They told me I had a gluten intolerance and I was starving to death, and then I went to the doctor later who said, ‘No, that’s not what’s wrong with you, you just need more fiber.”

M: [Another challenge is that] I know a lot of women want to go back to that man that was not right for them.

L: Yes, they do. They feel safe.

M: Having access to a therapist, when you’re released will help a lot. And I tell the ladies now, if you just go into one counseling session, just do it just to unpack some of that stuff that you dealt with when you’re in prison.

When I was incarcerated, if you weren’t on a mental health caseload, you couldn’t talk to anybody.

L: You couldn’t, because I remember going through those hoops as well. If you don’t come in with a mental health case when you come in, you’re jumping through hoops just trying to talk to somebody. A lot of stuff weighs on women, being in prison and being out of prison. We kind of feel like the world is on our shoulders a lot, and we feel like we have to show everybody that we’re strong, and we can do it. We take on way more than we absolutely should.

M: Yeah. I’m kind of glad that I did not go back [home] when I first came home because they would have been pulling me in different directions and it would have been too overwhelming.

L: I was really selfish in my first year home. I’m not really selfish towards myself, but selfish towards my family. When I got to the halfway house, my dad wasn’t doing well. I was avoiding talking to him because my dad was an alcoholic, and trying to wait a couple of weeks until I was off ankle monitors so I could go talk to him face to face. And he ended up passing away two weeks before I got off the ankle monitor. So after I was at home, I just was very selfish. I didn’t hang out with friends. I didn’t hang out with my extended family. All of my time was literally work, my husband, my kids, and nothing else.

I remember my brother being a little upset with me, but I remember explaining to him like I’m really sorry, but I’ve been gone for a couple years and I love you, but these relationships were harmed the most. These were the ones that needed my undivided attention. I remember my brother [was] like, man, I’m really sorry I didn’t think about it like that. Him and I are good now, but my kids and my husband came first. A lot of people don’t do that. They let their families pull them in multiple directions, especially if they don’t have a lot of help.

M: Right. So my son was 17. He was in his last year of school. He didn’t want to come up here in his last year, and once he graduated, he went off to the Navy. But I was still able to see him. I was at a transitional house and they would allow me to get a hotel room for the weekend. My family would pay for it.

And [you have to manage] your kids’ expectations too sometimes, because they want you to still spend the money that you did before you went in. Yeah, I realized I can’t spend this type of money anymore. That is not my lifestyle anymore. So we’re spending more time and he was okay with that. He really was.

L: It is your time that they want. We spent a lot of time at the park playing catch and walking the dog, and that actually made more of a difference than trying to spend money on them.

What are your dreams for the Chopping for Change program? Where do you see it in a couple years?

M: I want to see more women coming out, or at least most of the population that’s incarcerated in [Northeast Reintegration Center] and expanding out to the other women’s prisons in Ohio and possibly the nation. I also want to see them with jobs. One of the things that we’re working on is getting them to restaurants and making a wage and being able to have some money when they get out.

L: What about even having a Chopping for Change, like halfway house for those ladies, too?

M: That’s my personal future goal: to start having apartments and houses for women coming out of incarceration with families. That is one of my goals in life. I’m working on it.

L: Yeah, it’s kind of like, what about taking the next step so they have a place to live? So now they have a bank account to come out to, and a place where they’re not fighting to get approved and denied 8 million times, or paying tons of fees. That would be awesome. That really would be awesome.

Learn more about Chopping for Change, and donate to the program here. $325 can sponsor a woman productively re-entering society after incarceration.